BIZARRE MEDIEVAL MEDICAL PRACTICES

Medicine is one of the cornerstones of modern civilization - so much so that we take it for granted. It wasn’t always the case that you could just waltz into a doctor’s office to have them cure what ailed you. In medieval times, for example, things were a lot more dangerous, and a lot stranger.

Boar Bile Enemas

Enemas in medieval times were performed by devices called clysters. A clyster was a long metal tube with a cup on the end. The tube would be entered into the anus and a medicinal fluid poured into the cup. The fluid would then be introduced into the colon by a series of pumping actions. Although warm soapy water is used for enemas today, things were a little more earthy back then: one of the most common fluids finding its way into a clyster was a concoction of boar’s bile.

Even kings were high up on the clyster. King Louis XIV of France is said to have had over 2,000 enemas during his reign - some even administered while he sat on his throne.

Urine Was Used As An Antiseptic

Though it may not have been common, there is evidence to suggest that urine was occasionally used as an antiseptic in the Medieval Era. Henry VIII’s surgeon, Thomas Vicary, recommended that all battle wounds should be washed in urine. In 1666, the physician George Thomson recommended urine to be used on the plague. And there was even a bottled version: Essence Of Urine.

This isn’t quite as insane as it seems: urine is sterile when it leaves the body and may have been a healthier alternative than most water - which came with no such guarantee of cleanliness.

Eye Surgery (With A Needle)

During the Middle Ages, cataract surgery was performed with a thick needle. The procedure involved pushing the cornea to the back of the eye.

Of course, eye surgery changed rapidly once Islamic medicine began to influence European practices. Rather than a needle, a metal hypodermic syringe was inserted through the sclera (the white part of the eye) and then used to extract of cataracts via suction.

Hot Iron For Haemorrhoids

It was once believed that if a person did not pray to St. Fiacre (the “protector against haemorrhoids”) they would suffer from, you guessed it, haemorrhoids. If you were one of those unlucky fellows, you’d be sent off to the monks - who would put a red-hot iron up your anus. Nasty, but the less painful alternative was equally less effective: they’d send you to go and sit on St. Fiacre’s famous rock, the spot where the seventh-century Irish monk was miraculously cured of his haemorrhoids. It was for this reason that throughout the Middle Ages, haemorrhoids were called “Saint Fiacre’s illness.”

By the 12th century, things had changed. Jewish physician Moses Maimonides wrote a seven-chapter treatise on haemorrhoids calling into question the contemporary state of treatment. He prescribed a far simpler method: a good soak in a bath.

Deadly Surgery

Despite what blockbuster movies may have taught you, going under the knife without any anaesthetic wasn’t as common in the medieval period as some people claim. In fact, medicine throughout this time was quite progressive: as the world expanded and travellers came from far afield, doctors from two different cultures would often share notes, and new practices were constantly being put to use.

However, even if the will for better medical care was there, the knowledge of chemicals certainly wasn’t. Although anaesthetic was administered, analgesics, antibiotics, and disinfectants were a far cry from what they are today. As a result, many people died from infected wounds.

Poisonous Anaesthetics

As stated above, anaesthetics were far from the established science they are today. In fact, general anaesthesia is only about 150 years old. Before these advances, a rather crude brew of herbs mixed with wine was used to sedate the patient instead. The most common of these herbal anaesthetics was known as dwale.

There were numerous ingredients in dwale - from the innocuous, such as lettuce and vinegar, to the deadly, such hemlock and opium. Much like modern knockout drugs, mixing these ingredients incorrectly could result in the patient’s death.

Trepanning

Trepanning involved boring a small hole into the skull to expose the dura mater, the outer membrane of the brain. The practice was believed to alleviate pressure and treat health problems localized within the head, though it was also thought to cure epilepsy, migraines, and mental disorders and were a common “fix” for more physical problems such as skull fractures. Needless to say, such exposure of the brain to airborne germs would often be fatal.

Trepanning as a practice has not been completely abandoned: it was performed as recently as 2000 when two men in the US used it to treat a woman suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome and depression.

Surgery On The Battlefield

In medieval times, battlefield medicine was about as grisly as it gets, and arrows were one of the main culprits. Arrowheads were commonly attached to the shaft with wax for one single purpose: so that when the arrow was pulled out, the tip would break off inside the victim’s body. Purpose-built “arrow removers” - designed to pinch the tip and pull it from the body - were used to heal wounded soldiers. The wound was then cauterized with a red-hot iron to stop the bleeding and prevent infections.

While much has been forgotten about the medical capabilities of this era, research has shown that it may have been more effective than you might think. A set of bones from 500-700 AD discovered in Italy in 2011 showed that soldiers of that era could survive massive blows to the head. One of the remains even showed evidence that the individual had survived after suffering a five-centimetre (two-inch) hole to the head.

Medical Astrology

Back in medieval times, astrologers were so revered that many thought they were real-life magicians. The truth is, they were respected scholars who advised on increasing crop yield, predicted the weather, and informed a family-to-be what sort of personality their child would have. The latter would often have consequences for the child’s medical care.

Doctors would refer to special calendars that contained star charts in order to aid with diagnosis. By the 1500s, the physicians of Europe were legally required to assess a patient’s horoscope before embarking on any medical interference.

Astrology suggests that each body part is influenced by the sun, moon, and planets, and that each star sign presides over different parts of the body. Aries, for example, pertains to the head, face, brain, and eyes; whereas Scorpio represents the reproductive system, sexual organs, bowels and excretory system. After the patient’s star chart was examined and the current position of the stars was taken into account, a person’s ailment could be predicted and a diagnosis would be made.

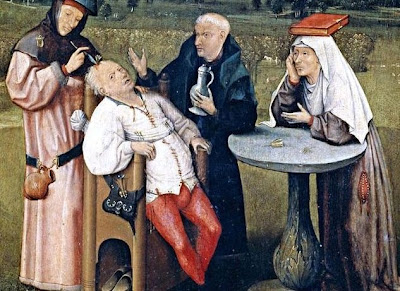

Bloodletting

Doctors of the medieval period believed in things called “humors.” The word “humors” referred to certain fluids found in the body: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. “Humorism” was developed from the musings of Greek and Roman physicians who believed an excess or deficiency of any of the four humors would strongly influence a person’s health.

For some reason, in the Middle Ages, blood - and excess blood in particular - was often seen as the cause of multiple ailments. Therefore, doctors would remove large quantities of blood from a person’s veins in the hope that it would cure them. The two main ways of doing this were leeching and venesection.

In leeching, a leech was placed on the part of the body that was a concern and the “blood-worm” would suck blood (and, in theory, the illness) from the patient. Venesection was a little bit more direct: a doctor would literally open up a vein using a knife called a “fleam” and allow blood to drain from the body.

Bloodletting was so common that some people drained their blood regularly just because they believed it would keep them healthy. Surely a half-hour jog is a better way to stay fit?

Comments

Post a Comment